Extracts of Clara Quien’s Talk on Modelling Mahatma Gandhi

How did I meet Gandhi and get the permission to model him? The story really began in Italy, when I had a vision of a Pietà, which I later executed in Kashmir in 1941, urged by the terrible suffering caused by the war. Kumarappa, the organiser of AVIA (All India Village Industries Association) saw the monument LOVE ONE ANOTHER, was very much impressed and said: “We will see what we can do about it.” To my great surprise Kumarappa wrote that Gandiji was interested and wanted the Christ statue for their headquarters in Maganwardi, Warda. Someone offered a good donation and my expenses. I was to choose the site and install the statue. “Will the Mahatma be there so he can sit for me?” – “It would be much appreciated, we will ask him.”

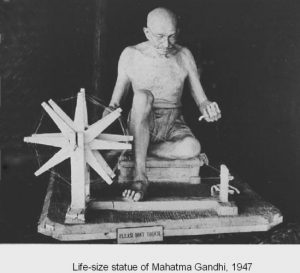

I planned to do a life size statue of Gandhi at the spinning wheel. (It was he who re-introduced hand-spinning and weaving to undermine the British imports and defied the law in so doing). To save time while waiting for Gandhi’s arrival from Madras, I started doing some preliminary work… Gandhi’s train was eleven hours late because enthusiastic villagers en route had thrown themselves before the advancing engine again and again, as was their desire, in order to greet the Mahatma and present him with their last bit of jewellery or their year’s savings. On that trip Rs 35,000 were presented to him. This happened continually, wherever he went, as everyone knew that he never used any of the gifts for himself, but only to help educate and raise the people out of their abject poverty and work for their independence. The railway authorities often offered him a special train free of charge on account of these continual interruptions, but he insisted travelling third class on an ordinary train and only someone who has thus travelled in India knows what that meant. He would also insisted on living in the town’s sweeper communities when he visited places, which again caused their authorities no end of trouble, as they often had to re-build the terribly decrepit, stench- and vermin-infested hovels these outcasts or pariahs lived in.

I planned to do a life size statue of Gandhi at the spinning wheel. (It was he who re-introduced hand-spinning and weaving to undermine the British imports and defied the law in so doing). To save time while waiting for Gandhi’s arrival from Madras, I started doing some preliminary work… Gandhi’s train was eleven hours late because enthusiastic villagers en route had thrown themselves before the advancing engine again and again, as was their desire, in order to greet the Mahatma and present him with their last bit of jewellery or their year’s savings. On that trip Rs 35,000 were presented to him. This happened continually, wherever he went, as everyone knew that he never used any of the gifts for himself, but only to help educate and raise the people out of their abject poverty and work for their independence. The railway authorities often offered him a special train free of charge on account of these continual interruptions, but he insisted travelling third class on an ordinary train and only someone who has thus travelled in India knows what that meant. He would also insisted on living in the town’s sweeper communities when he visited places, which again caused their authorities no end of trouble, as they often had to re-build the terribly decrepit, stench- and vermin-infested hovels these outcasts or pariahs lived in.

Then, contrary to expectations, it became evident that Gandhiji was not coming to Magavardi, but stayed at Sevagram Ashram five miles away. I begged to be allowed to go there and departed in a little two-wheeled pony-cart with sack, pack, baby and pram; the unfinished 1400lb model was to follow later by oxcart. Just then I was told that Gandhi was to leave again, four days sooner than planned, which gave me a week in which to complete the work. Though a quick worker, it seemed a superhuman task and I became anxious, especially since I had no one to look after baby Rhea.

A precious day passed and the statue failed to arrive. What could have caused the delay? They phoned: “The model could not be transported by bullock cart, as it was too large and heavy. We had to obtain permission to transport it by truck, over this narrow dirt-road.” It came late that night. (There were further delays before Clara could commence work seriously. She lost her temper, demanding all kinds of things. Gandhi reprimanded her.)

In this depressed mood, I had entered Gandhiji’s bare room and he calmed down my ruffled feelings. He was so genuinely natural, frankly amused, truly spontaneous and straightforward. Later Gandhi went spinning. Silently we worked together. The likeness began to appear. When he noticed it, I asked if he liked it. “You have spun a little” he said, and smiled.

That evening I went to a communal prayer, because the weird, soft music and lively singing I had heard sometimes from afar, intrigued me. The congregation sat under the stars on little mats arranging themselves in a square. Gandhiji sat at the head, to his left were the women, to his right the men and opposite him the musicians and singers. First they hummed softly, the sound gradually swelling and becoming more forceful. Later the congregation joined in singing the names of God and clapping their hands rhythmically. I belong to no organised religion but visit services of various faiths occasionally. Never had I encountered such joyful and carefree prayer. I was pleasantly surprised to hear a Mahomedan chant and a Zoroastrian hymn and was told that they also often had Christian songs. As they do not sit in a temple, mosque or church, no-one can take offence. As every religion was respected, people of every faith joined in. “There are many roads to the same God.”

Next morning while at work Gandhiji asked me if I was comfortable. “Thank you, I am very happy I came here.” Gandhiji’s spinning had done something to me. Silently and patiently that busy man sat spinning every day, never perturbed when the thread broke or the old-fashioned wheel got out of order. How long now, thirty, forty years? When did he realise that the spinning wheel was more powerful than arms and munitions? Would he spin until the day of his death or until he had attained his fondest wish? It seemed that by leading an exemplary life with unfaltering purpose, never wearying, one single man, plain, poor and simple, but gentle and kind and loving, should attain what he had. “He has made us into a nation”, a Mahomedan Shiah said.

He ate his midday meal out of a shallow wooden bowl while I observed the extraordinary mobility of his face. A gruel of crushed wheat and a few peeled oranges were his daily fare, his other meals being as frugal. On this diet he rose at 4.30 a.m., retired at 9 p.m. and his day was filled with interviews, meetings, dictation letters, reading and planning. During his short afternoon nap he was being massaged and he even cut his toenails in company. That at the age of 76! He must have had a wonderful constitution.

That evening Babuji (Gandhi) passed by my hut and was delighted to see baby Rhea. “What a lovely baby you have! Now you should model her, not me!” – “I did when she was three weeks old.” “She is a prize baby” he remarked. I told him that our second child had indeed won first prize in a toddler’s show with ‘Vegetarian specimen’ pinned on his back. He laughed: “How many children do you have?” “Three.” “Then why do you make models if you have such lovely children? They are live models. Better share out your clay for the people to wash themselves with.” Gandhiji also enjoyed the fact that I spoke Hindi.

Next day was Monday and I noticed that Gandhiji did not speak but nodded his head in assent and shook it for denial and I was told that this was his weekly day of silence. He continued his usual activities and everyone spoke to him. Occasionally he wrote a few words. That very day the Viceroy’s Secretary chose to visit the Mahatma. A most Important Personage, as he arrived by air, thereafter being driven to the little man’s mud hut in a super luxurious Rolls Royce limousine. It was really wonderful to see Gandhi keeping his silence, when the representative of the highest Imperial Authority visited him: the instigator of the nationalistic movement who had so often been put to prison by these very authorities. Yet so powerful by his uncompromising non-violent stand, that they had to come to his humble dwelling. He listened and they both returned to the limousine. Gandhi roared with laughter whereas the immaculately dressed Englishman only smiled restrainedly.

Later I worked on the body part of the statue for several hours in the moonlight from memory because they only had small oil lamps. I felt I could complete his head in the morning, and then the whole figure. However, I was unfortunately told that there were two cases of mumps in the compound and that I would do well to leave for the baby’s sake. So I only finished the head and bust before a conveyance arrived.

“Gandhiji, I have come to say good-bye. I hope you will allow me to come back in December?”

“Gandhiji, I have come to say good-bye. I hope you will allow me to come back in December?”

“Then you must learn to spin!”

“I have already started…”

“That’s fine. But I cannot say “yes” because I’m not my own master and don’t know where I will be then.”

“Thank you very much for everything, Babuji.” He shook my proferred hand heartily.

The Mahatma laid down a few simple rules for himself to which he stuck with persistent tenacity. Never during my short stay and subsequent visits did I see him loose his temper and throughout his brimful day he was always mild and gentle. Sometimes I saw his face wear such an expression of infinite sadness in a rare moment that he was not externally occupied, that I marvelled at his sudden outbursts of friendly, hearty laughter. Though I modelled him from life on two other occasions, I was only able to complete the statue of him at the spinning wheel on the first anniversary day of his tragic assassination when India and all the world mourned him. His likeness was garlanded with flowers.

Copyright © Rhea Quien 2006, Cambridge